Decorating IO Streams

The Purpose of Decoration

The Decorator Pattern is one of the 23 Design Patterns from the Gang of Four. The Java I/O API uses this pattern to extend or modify the behavior of some of its classes.

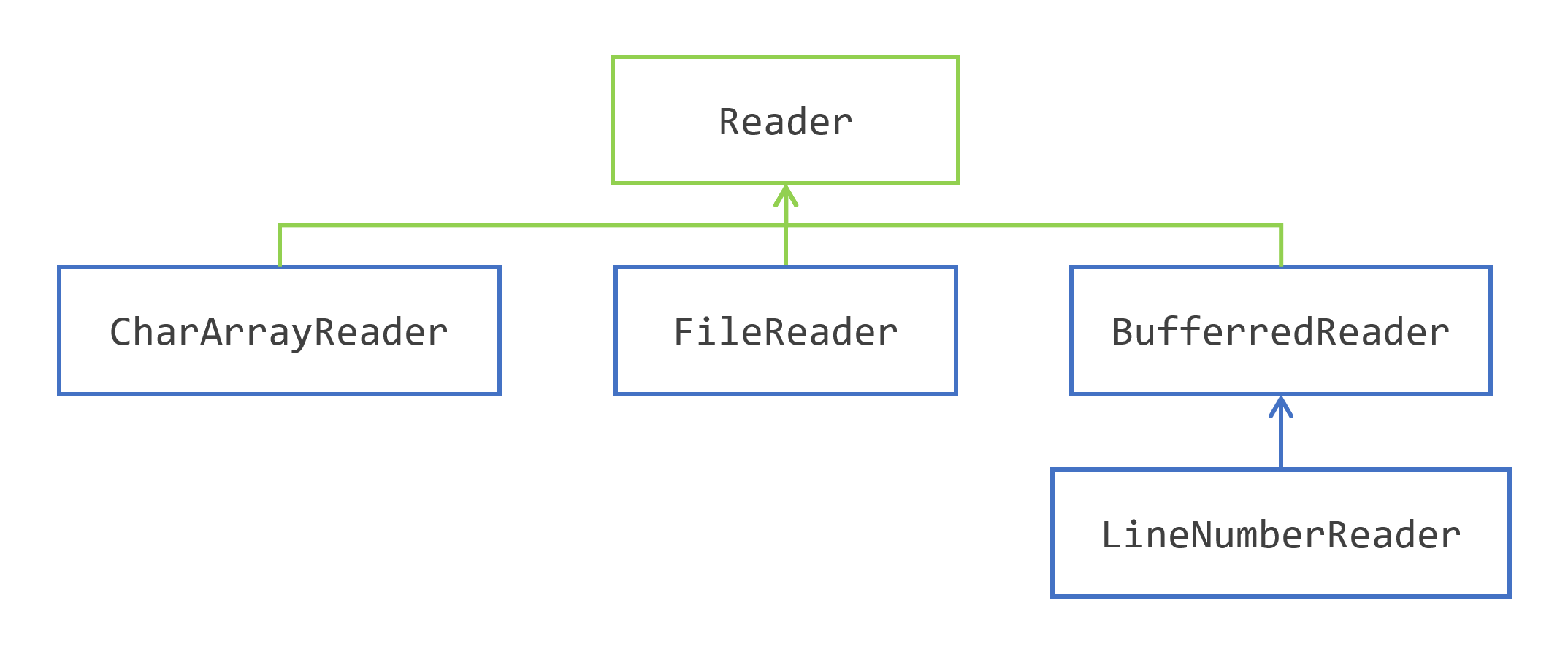

The Reader class hierarchy illustrates how decoration has been used to design Java I/O.

The Reader class is an abstract class that defines reading characters can be done. It is extended by three concrete classes: CharArrayReader, StringReader (not shown on this diagram) and FileReader that provide a medium from which the characters are read.

Then BufferedReader extends Reader and decorates it. To create an instance of BufferedReader, you must provide a Reader object that acts as a delegate for the BufferedReader object. The BufferedReader class

then adds several methods to the base Reader class.

The decoration of the BufferedReader class allows for the overriding of the existing concrete methods of the Reader class, as well as the addition of new methods.

The same goes for the LineNumberReader class, that extends BufferedReader and needs an instance of Reader to be constructed.

Writing and Reading Characters to Binary Streams

You saw in the introduction of this section that the classes of the Java I/O API is divided into two categories, one to handle characters and the other to handle bytes. It would not make sense to try to read or write bytes from text files. But writing characters to binary files is something that is widely used in applications.

The Java I/O API gives two classes for that:

InputStreamReaderis a reader that can read characters from anInputStream, andOutputStreamWriteris a writer that can write characters to anOutputStream.

InputStreamReader is a decoration of the Reader class, built on an InputStream object. You can provide a charset if needed. The same goes for the OutputStreamWriter class, that extends the Writer and that needs an OutputStream object to be built.

Writing Characters using an OutputStreamWriter

Let us use an OutputStreamWriter to write a message to a text file.

String message = """

From fairest creatures we desire increase,

That thereby beauty's rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease

His tender heir might bear his memory:

But thou, contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed'st thy light's flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies,

Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel.

Thou that art now the world's fresh ornament,

And only herald to the gaudy spring,

Within thine own bud buriest thy content,

And, tender churl, mak'st waste in niggardly.

Pity the world, or else this glutton be,

To eat the world's due, by the grave and thee.""";

Path path = Path.of("files/sonnet.txt");

try (var outputStream = Files.newOutputStream(path);

var writer = new OutputStreamWriter(outputStream);) {

writer.write(message);

} catch (IOException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

long size = Files.size(path);

IO.println("size = " + size);

Running this code will create a file named sonnet.txt in the files directory with the text of the first sonnet of Shakespeare.

Several things are worth noting in this example.

- The

OutputStreamWriteris created by decorating theOutputStreamcreated with the factory method from theFilesclass. - Both the output stream and the writer are created as arguments of the try-with-resources pattern, thus ensuring that they will be both flushed and closed in the right order. If you miss that, you may have missing characters in your file, just because an internal buffer has not been properly flushed.

Running this code displays the following result.

size = 609

Reading Characters using an InputStreamReader

Reading the sonnet.txt file that you created in the previous section follows the same pattern. Here is the code.

Path path = Path.of("files/sonnet.txt");

String sonnet = null;

try (var inputStream = Files.newInputStream(path);

var reader = new InputStreamReader(inputStream);

var bufferedReader = new BufferedReader(reader);

Stream<String> lines = bufferedReader.lines();) {

sonnet = lines.collect(Collectors.joining("\n"));

} catch (IOException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

IO.println("sonnet = \n" + sonnet);

The reader object is created by decorating the inputStream object, just as previously. This code goes a little further though.

- It decorates this plain

readerobject to create aBufferedReader. TheBufferedReaderclass has several methods to read a text file line by line, which we are going to use in this example. - It calls the

lines()method on theBufferedReaderobject. This method returns a stream of the lines of this text file. Because stream implementsAutoCloseable, you can create it as an argument of this try-with-resources pattern.

Collecting the stream with the Collectors.joining() collector is a very easy way to concatenate all the elements of this stream, separated with a newline (in this example).

Running this code produces the following result.

sonnet =

From fairest creatures we desire increase,

That thereby beauty's rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease

His tender heir might bear his memory:

But thou, contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed'st thy light's flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies,

Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel.

Thou that art now the world's fresh ornament,

And only herald to the gaudy spring,

Within thine own bud buriest thy content,

And, tender churl, mak'st waste in niggardly.

Pity the world, or else this glutton be,

To eat the world's due, by the grave and thee.

Handling Compressed Binary Streams

The Decorator pattern is used in a very efficient way to read and write gzip files. Gzip is an implementation of the deflate algorithm. This format is specified the the RFC 1952. Two classes implement this algorithm in the JDK: GZIPInputStream and GZIPOutputStream.

These two classes are extensions of the base classes InputStream and OutputStream. They just override the reading and the writing of bytes, without adding any method. Decoration is used here to override a default behavior.

Thanks to the decorator pattern, modifying the two previous example to write and read this text in a compressed file is just a small modification of the code.

Writing Data with a GzipOutputStream

Here is the code you can use to write text to a gzip file.

String message = ...; // the same sonnet as previously

Path path = Path.of("files/sonnet.txt.gz");

try (var outputStream = Files.newOutputStream(path);

var gzipOutputStream = new GZIPOutputStream(outputStream);

var writer = new OutputStreamWriter(gzipOutputStream);) {

writer.write(message);

} catch (IOException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

long size = Files.size(path);

IO.println("size = " + size);

Note that the gzipOutputStream object is created by decorating the regular outputStream, and is used to create the writer object. Nothing else is changed in the code.

Because this file is now compressed, its size is smaller. Running this code displays the following.

size = 377

Note that you can open this file with any software capable of reading gzip files.

Reading Data with a GzipInputStream

The following code reads the text back.

Path path = Path.of("files/sonnet.txt.gz");

String sonnet = null;

try (var inputStream = Files.newInputStream(path);

var gzipInputStream = new GZIPInputStream(inputStream);

var reader = new InputStreamReader(gzipInputStream);

var bufferedReader = new BufferedReader(reader);

var stream = bufferedReader.lines();) {

sonnet = stream.collect(Collectors.joining("\n"));

} catch (IOException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

IO.println("sonnet = \n" + sonnet);

Note that the gzipInputStream object is created by decorating the regular inputStream. This gzipInputStream object is then decorated to create the reader object. The rest of the code is unchanged.

Handling Streams of Primitive Types

The Java I/O API offers two more decorations of InputStream and OutputStream: DataInputStream and DataOutputStream.

These classes add methods to read and write primitive types on binary streams.

Writing Primitive Types

The DataOutputStream class delegates all its write operations to the instance of OutputStream it wraps. This class provides the following methods to write primitive types:

writeByte(int): writes the eight low-order bits of the argument to the underlying stream. The 24 high-order bits of the argument are ignored.

These other methods are self-explanatory.

writeBoolean(boolean)writeChar(char)writeShort(short)writeInt(int)writeLong(long)writeFloat(float)writeDouble(double)

The DataOutputStream class also provides methods to write bytes and chars from arrays.

writeBytes(String): writes the characters of the string as a sequence of bytes. Each byte corresponds to the 8 low-order bits of each character. The 8 high-order bits are ignored.writeChars(String): writes the characters of the string.writeUTF(String): writes a string to the underlying output stream usingmodified UTF-8 encoding.

The following code writes 6 ints to a binary file.

int[] ints = {3, 1, 4, 1, 5, 9};

Path path = Path.of("files/ints.bin");

try (var outputStream = Files.newOutputStream(path);

var dataOutputStream = new DataOutputStream(outputStream);) {

for (int i : ints) {

dataOutputStream.writeInt(i);

}

} catch (IOException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

System.out.printf("Wrote %d ints to %s [%d bytes]\n",

ints.length, path, Files.size(path));

Running this code displays the following.

Wrote 6 ints to files\ints.bin [24 bytes]

Because each an int is 4 bytes, the size of the file is 24 bytes, as shown on the console.

Reading Primitive Types

The DataInputStream reads primitives types from binary streams. It decorates an InputStream that you must provide to construct any instance of DataInputStream. This new instance delegates all the read operations to the InputStream you gave.

It provides the following methods, which are self-explanatory. Each method returns the corresponding type.

It provides method to read unsigned bytes and shorts:

readUnsignedByte(): reads one single unsigned byte and returns in the form of anintin the range 0 through 255.readUnsignedShort(): reads two bytes and decodes them as an unsigned 16-bits integer. The value is returned as anintin the range 0 to 65535.

It also provides methods to read several bytes and arrange them in a string of characters.

readUTF(): this method reads a string of characters encoded in modified UTF-8 format.readFully(byte[]): this method reads bytes from the input stream and stores them in the provided array. It will try to fill the array, and will block if needed. It will throw andEOFExceptionIf the end of the stream is met before the array has been filled.readFully(byte[], int offset, int length): does the same as the previous method, fillinglengthbytes starting at the providedoffset.

Here is the code you can write to read the integers you wrote in the file created in the previous example.

Path path = Path.of("files/ints.bin");

int[] ints = new int[6];

try (var inputStream = Files.newInputStream(path);

var dataInputStream = new DataInputStream(inputStream);) {

for (int index = 0; index < ints.length; index++) {

ints[index] = dataInputStream.readInt();

}

IO.println("ints = " + Arrays.toString(ints));

} catch (IOException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

Last update: January 25, 2023