Creating and Using Objects

Understanding What Objects Are

A typical Java program creates many objects, which as you know, interact by invoking methods. Through these object interactions, a program can carry out various tasks, such as implementing a GUI, running an animation, or sending and receiving information over a network. Once an object has completed the work for which it was created, its resources are recycled for use by other objects.

Here is a small program, called CreateObjectDemo, that creates three objects: one Point object and two Rectangle objects. You will need all three source files to compile this program.

public class CreateObjectDemo {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Declare and create a point object and two rectangle objects.

Point originOne = new Point(23, 94);

Rectangle rectOne = new Rectangle(originOne, 100, 200);

Rectangle rectTwo = new Rectangle(50, 100);

// display rectOne's width, height, and area

IO.println("Width of rectOne: " + rectOne.width);

IO.println("Height of rectOne: " + rectOne.height);

IO.println("Area of rectOne: " + rectOne.getArea());

// set rectTwo's position

rectTwo.origin = originOne;

// display rectTwo's position

IO.println("X Position of rectTwo: " + rectTwo.origin.x);

IO.println("Y Position of rectTwo: " + rectTwo.origin.y);

// move rectTwo and display its new position

rectTwo.move(40, 72);

IO.println("X Position of rectTwo: " + rectTwo.origin.x);

IO.println("Y Position of rectTwo: " + rectTwo.origin.y);

}

}

Here is the Point class:

public class Point {

public int x = 0;

public int y = 0;

// a constructor!

public Point(int a, int b) {

x = a;

y = b;

}

}

And the Rectangle class:

public class Rectangle {

public int width = 0;

public int height = 0;

public Point origin;

// four constructors

public Rectangle() {

origin = new Point(0, 0);

}

public Rectangle(Point p) {

origin = p;

}

public Rectangle(int w, int h) {

origin = new Point(0, 0);

width = w;

height = h;

}

public Rectangle(Point p, int w, int h) {

origin = p;

width = w;

height = h;

}

// a method for moving the rectangle

public void move(int x, int y) {

origin.x = x;

origin.y = y;

}

// a method for computing the area of the rectangle

public int getArea() {

return width * height;

}

}

This program creates, manipulates, and displays information about various objects. Here's the output:

Width of rectOne: 100

Height of rectOne: 200

Area of rectOne: 20000

X Position of rectTwo: 23

Y Position of rectTwo: 94

X Position of rectTwo: 40

Y Position of rectTwo: 72

Try inside the Java Playground

Experiment with the Point and Rectangle classes:

The following three sections use the above example to describe the life cycle of an object within a program. From them, you will learn how to write code that creates and uses objects in your own programs. You will also learn how the system cleans up after an object when its life has ended.

Creating Objects

As you know, a class provides the blueprint for objects; you create an object from a class. Each of the following statements taken from the CreateObjectDemo program creates an object and assigns it to a variable:

Point originOne = new Point(23, 94);

Rectangle rectOne = new Rectangle(originOne, 100, 200);

Rectangle rectTwo = new Rectangle(50, 100);

The first line creates an object of the Point class, and the second and third lines each create an object of the Rectangle class.

Each of these statements has three parts (discussed in detail below):

- Declaration: The code set in bold are all variable declarations that associate a variable name with an object type.

- Instantiation: The

newkeyword is a Java operator that creates the object. - Initialization: The

newoperator is followed by a call to a constructor, which initializes the new object.

Declaring a Variable to Refer to an Object

Previously, you learned that to declare a variable, you write:

type name;

This notifies the compiler that you will use name to refer to data whose type is type. With a primitive variable, this declaration also reserves the proper amount of memory for the variable.

You can also declare a reference variable on its own line. For example:

Point originOne;

If you declare originOne like this, its value will be undetermined until an object is actually created and assigned to it. Simply declaring a reference variable does not create an object. For that, you need to use the new operator, as described in the next section. You must assign an object to originOne before you use it in your code. Otherwise, you will get a compiler error.

A variable in this state, currently references no object.

Instantiating a Class

The new operator instantiates a class by allocating memory for a new object and returning a reference to that memory. The new operator also invokes the object constructor.

Note: The phrase "instantiating a class" means the same thing as "creating an object." When you create an object, you are creating an "instance" of a class, therefore "instantiating" a class.

The new operator requires a single, postfix argument: a call to a constructor. The name of the constructor provides the name of the class to instantiate.

The new operator returns a reference to the object it created. This reference is usually assigned to a variable of the appropriate type, like:

Point originOne = new Point(23, 94);

The reference returned by the new operator does not have to be assigned to a variable. It can also be used directly in an expression. For example:

int height = new Rectangle().height;

This statement will be discussed in the next section.

Initializing an Object

Here is the code for the Point class:

public class Point {

public int x = 0;

public int y = 0;

//constructor

public Point(int a, int b) {

x = a;

y = b;

}

}

This class contains a single constructor. You can recognize a constructor because its declaration uses the same name as the class and it has no return type. The constructor in the Point class takes two integer arguments, as declared by the code (int a, int b). The following statement provides 23 and 94 as values for those arguments:

Point originOne = new Point(23, 94);

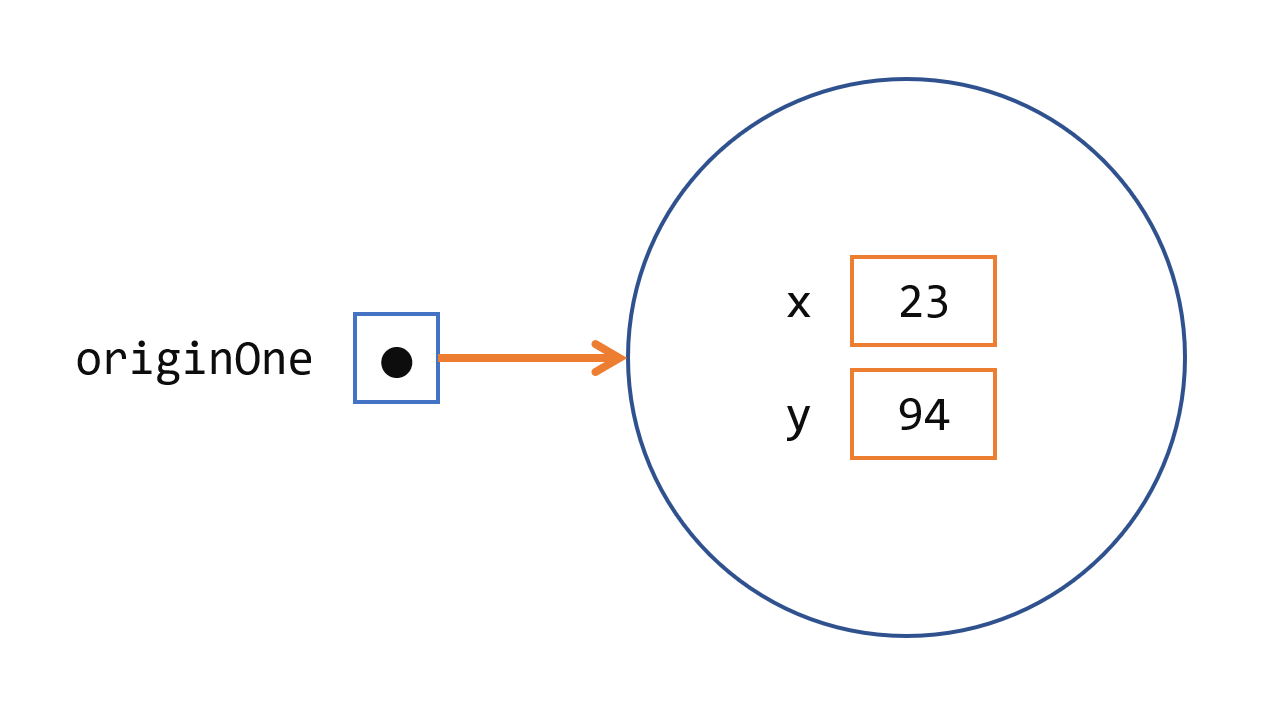

The result of executing this statement can be illustrated in the next figure:

Here is the code for the Rectangle class, which contains four constructors:

public class Rectangle {

public int width = 0;

public int height = 0;

public Point origin;

// four constructors

public Rectangle() {

origin = new Point(0, 0);

}

public Rectangle(Point p) {

origin = p;

}

public Rectangle(int w, int h) {

origin = new Point(0, 0);

width = w;

height = h;

}

public Rectangle(Point p, int w, int h) {

origin = p;

width = w;

height = h;

}

// a method for moving the rectangle

public void move(int x, int y) {

origin.x = x;

origin.y = y;

}

// a method for computing the area of the rectangle

public int getArea() {

return width * height;

}

}

Each constructor lets you provide initial values for the rectangle's origin, width, and height, using both primitive and reference types. If a class has multiple constructors, they must have different signatures. The Java compiler differentiates the constructors based on the number and the type of the arguments. When the Java compiler encounters the following code, it knows to call the constructor in the Rectangle class that requires a Point argument followed by two integer arguments:

Rectangle rectOne = new Rectangle(originOne, 100, 200);

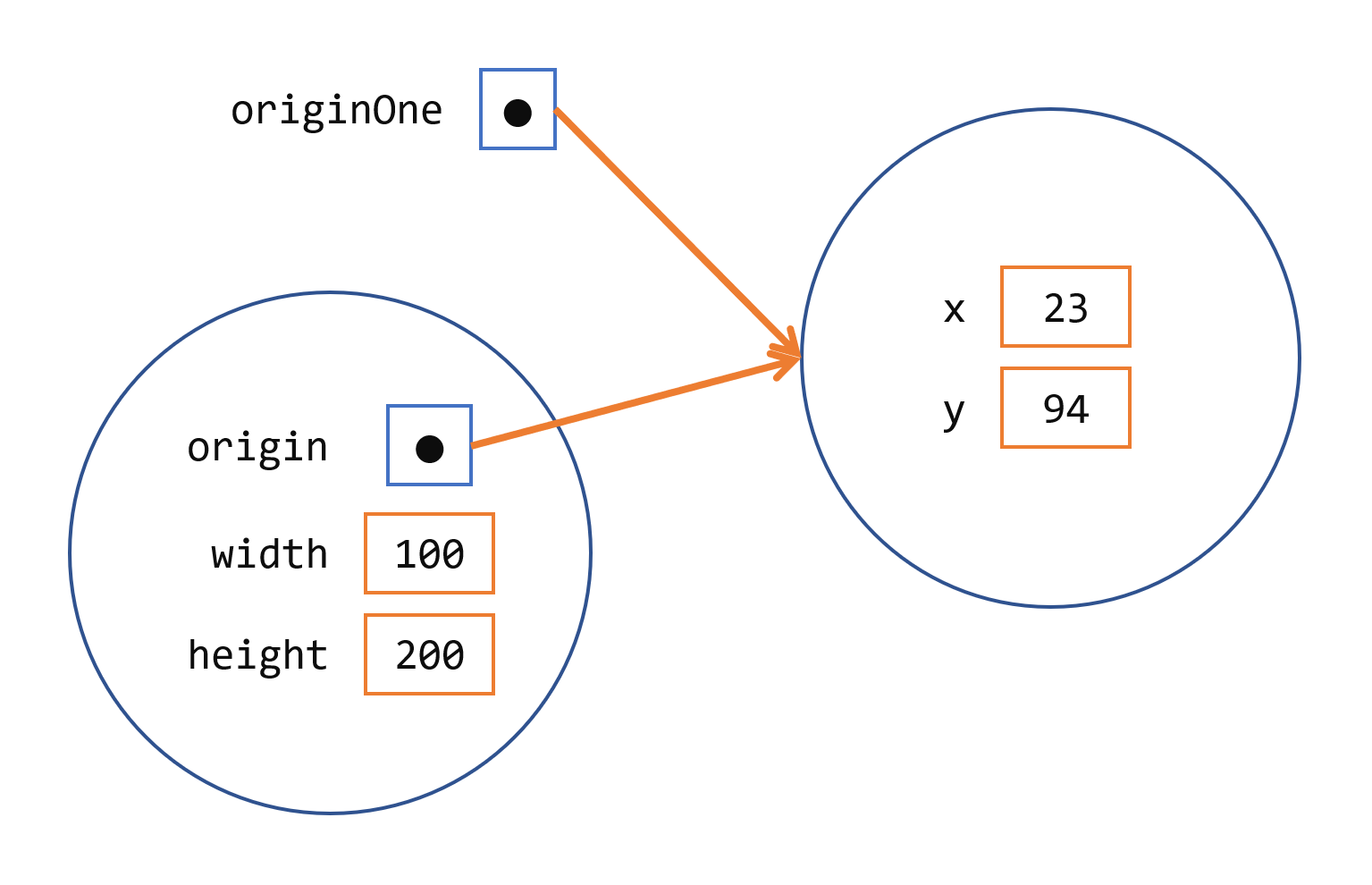

This calls one of Rectangle's constructors that initializes origin to originOne. Also, the constructor sets width to 100 and height to 200. Now there are two references to the same Point object—an object can have multiple references to it, as shown in the next figure:

The following line of code calls the Rectangle constructor that requires two integer arguments, which provide the initial values for width and height. If you inspect the code within the constructor, you will see that it creates a new Point object whose x and y values are initialized to 0:

Rectangle rectTwo = new Rectangle(50, 100);

The Rectangle constructor used in the following statement does not take any arguments, so it is called a no-argument constructor:

Rectangle rect = new Rectangle();

All classes have at least one constructor. If a class does not explicitly declare any, the Java compiler automatically provides a no-argument constructor, called the default constructor. This default constructor calls the class parent's no-argument constructor, or the Object constructor if the class has no other parent. If the parent has no constructor (Object does have one), the compiler will reject the program.

Practice with Different Constructors

Experiment with different ways to create objects using various constructors:

Using Objects

Once you have created an object, you probably want to use it for something. You may need to use the value of one of its fields, change one of its fields, or call one of its methods to perform an action.

Referencing an Object's Fields

Object fields are accessed by their name. You must use a name that is unambiguous.

You may use a simple name for a field within its own class. For example, we can add a statement within the Rectangle class that prints the width and height:

IO.println("Width and height are: " + width + ", " + height);

In this case, width and height are simple names.

Code that is outside the object's class must use an object reference or expression, followed by the dot (.) operator, followed by a simple field name, as in:

objectReference.fieldName

For example, the code in the CreateObjectDemo class is outside the code for the Rectangle class. So to refer to the origin, width, and height fields within the Rectangle object named rectOne, the CreateObjectDemo class must use the names rectOne.origin, rectOne.width, and rectOne.height, respectively. The program uses two of these names to display the width and the height of rectOne:

IO.println("Width of rectOne: " + rectOne.width);

IO.println("Height of rectOne: " + rectOne.height);

Attempting to use the simple names width and height from the code in the CreateObjectDemo class does not make sense — those fields exist only within an object — and results in a compiler error.

Later, the program uses similar code to display information about rectTwo. Objects of the same type have their own copy of the same instance fields. Thus, each Rectangle object has fields named origin, width, and height. When you access an instance field through an object reference, you reference that particular object's field. The two objects rectOne and rectTwo in the CreateObjectDemo program have different origin, width, and height fields.

To access a field, you can use a named reference to an object, as in the previous examples, or you can use any expression that returns an object reference. Recall that the new operator returns a reference to an object. So you could use the value returned from new to access a new object's fields:

int height = new Rectangle().height;

This statement creates a new Rectangle object and immediately gets its height. In essence, the statement calculates the default height of a Rectangle. Note that after this statement has been executed, the program no longer has a reference to the created Rectangle, because the program never stored the reference anywhere. The object is unreferenced, and its resources are free to be recycled by the Java Virtual Machine.

Calling an Object's Methods

You also use an object reference to invoke an object's method. You append the method's simple name to the object reference, with an intervening dot operator (.). Also, you provide, within enclosing parentheses, any arguments to the method. If the method does not require any arguments, use empty parentheses.

objectReference.methodName(argumentList);

or:

objectReference.methodName();

The Rectangle class has two methods: getArea() to compute the rectangle's area and move() to change the rectangle's origin. Here's the CreateObjectDemo code that invokes these two methods:

IO.println("Area of rectOne: " + rectOne.getArea());

...

rectTwo.move(40, 72);

The first statement invokes rectOne's getArea() method and displays the results. The second line moves rectTwo because the move() method assigns new values to the object's origin.x and origin.y.

As with instance fields, objectReference must be a reference to an object. You can use a variable name, but you also can use any expression that returns an object reference. The new operator returns an object reference, so you can use the value returned from new to invoke a new object's methods:

new Rectangle(100, 50).getArea()

The expression new Rectangle(100, 50) returns an object reference that refers to a Rectangle object. As shown, you can use the dot notation to invoke the new Rectangle's getArea() method to compute the area of the new rectangle.

Some methods, such as getArea(), return a value. For methods that return a value, you can use the method invocation in expressions. You can assign the return value to a variable, use it to make decisions, or control a loop. This code assigns the value returned by getArea() to the variable areaOfRectangle:

int areaOfRectangle = new Rectangle(100, 50).getArea();

In this case, the object that getArea() is invoked on is the rectangle returned by the constructor.

The Garbage Collector

Some object-oriented languages require that you keep track of all the objects you create and that you explicitly destroy them when they are no longer needed. Managing memory explicitly is tedious and error-prone. The Java platform allows you to create as many objects as you want (limited, of course, by what your system can handle), and you do not have to worry about destroying them. The Java runtime environment deletes objects when it determines that they are no longer being used. This process is called garbage collection.

An object is eligible for garbage collection when there are no more references to that object. References that are held in a variable are usually dropped when the variable goes out of scope. Or, you can explicitly drop an object reference by setting the variable to the special value null. Remember that a program can have multiple references to the same object; all references to an object must be dropped before the object is eligible for garbage collection.

The Java runtime environment has a garbage collector that periodically frees the memory used by objects that are no longer referenced. The garbage collector does its job automatically when it determines that the time is right.

Last update: January 5, 2024